Assumptions, Photography and the Micro Four-Thirds System

About three years ago, renowned wedding photographer Bradley Hanson wrote this magnificent piece on assumptions and misconceptions in Photography, to be published in the very first edition of our monthly magazine.

Since that time, much has changed in the Photography industry, new technological advances have been introduced, and several new pieces of equipment launched. But, in essence, Photography remains exactly the same, and this article is more current than ever. So we thought of publishing this article again, but this time here on the website.

With our personal recommendation, this is an essential read for all photographers, regardless of the brand and system they use.

Maurício & Hugo

The Olympus Passion editors

Assumptions, Photography and the Micro Four-Thirds System

I have been photographing professionally for 18 years, mostly weddings, portraits and many years ago, for weekly newspapers. I’ve used everything from 4×5 view cameras, every medium format film size, 35mm film for years, and most digital formats. I used the Fujifilm X-system for 4 years. I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again here: I take the same photographs, regardless of the camera or phone I’m using. A new camera will not change your life or make you a better photographer. The role of photographic tools is to make your job more satisfying and/or to get out of the way of the artist controlling it. I have no interest in “converting” anyone to specific equipment or suggesting that using the tools I use will be ideal for your purposes, nor am I interested in adding to the long list of “switching” articles.

Cameras are like guitars and bicycles: what is “best” for you depends on your needs, your experience level and your patience.

This article is merely sharing my current thoughts about photography and maybe shattering a myth or two about equipment, particularly with the under appreciated Micro Four Thirds system.

We live in an era where we take for granted that we can figure out anything either by Googling it or watching a YouTube video. “Surely, someone else has figured this out.” This make sense when you are assembling a specific piece of furniture or trying to figure out how to clean unusual fabrics. When it comes to photography and the visual arts, that’s when things start to become more ambiguous.

This is also a time when it’s assumed by many that we can rely on “experts” to determine what will best suit or needs. It’s true that we can learn from others without having to experience everything firsthand. I don’t need to get polio to know that I don’t want it. I’ve read and written many articles describing my experience and feelings out specific photographic tools. In each case, I’ve been clear that photographic tools are way down on the list of the creative process and that what works for me doesn’t mean it’s going to be just as ideal for the person reading my review. We all come from different backgrounds and experience levels, and we all place value on differing qualities. We don’t agree on what photographs and photographers we like, so why would anyone expect that reviews are sacrosanct or should dictate what tools a photographer should choose? Because of that belief, I approach my reviews by discussing my experience, the things I value, and what is important to me.

I don’t have any secrets about what I do and I’m always happy to answer questions about photography. Instead of composition, lighting and subject matter, most of them, understandably, are about cameras and lenses because that is the entry point for so many people. “I heard this is good or this isn’t good for this,” etc. There is also an underlying, repeated theme in the kind of questions I get from other photographers, both publicly and privately, that one of the secrets to “success” in photography is just having the “right” gear or taking the right workshop, as though artistic satisfaction and knowledge of the art and craft of photography can be quickly bypassed through secret channels. Let me shatter that illusion for you. The best way to learn something is to do it yourself, not to hear it from another person. There is no substitute for putting in your time, making mistakes, taking your lumps, figuring out what works and what doesn’t, and developing your own style after taking countless frames. Malcolm McDowell suggests the 10,000 hour “rule,” others have proposed similar milestones. In photography, the photographer with desire to improve and the eye to study his/her own successes and failures will continue to improve. Plateaus are inevitable, but studying your own work and the work of photographers you admire will be the best teacher. There is no substitute for doing.

“Your first 10,000 photographs are your worst.”

– Henri Cartier-Bresson

Consciously or subconsciously, we all make assumptions about things we encounter during the day. Other people’s intentions, stereotypes, locations, regional differences, etc. There are a number of assumptions about photographic equipment, too.

Mention the words “Leica” and certain assumptions about German “craftsmanship” and quality immediately come to mind for most readers. These same feelings come up with Hasselblad, just substitute Sweden for Germany and add preconceived ideas about Zeiss lenses.

To give another example of the power of assumptions, there was a time when Leica was making cameras in both Canada and Portugal, particularly in the early 1980s when Leica was nearing bankruptcy. Articles on various photography sites like photo.net decried a perceived downward lack of quality, despite no evidence suggesting any such change (in fact, manufacturing process is largely identical, just a different location), and both Canada and Portugal are wonderful places with properly paid workers. Because manufacturing labeling laws vary from country to country, in theory, a camera can be made out of Chinese parts and then assembled in Germany and the camera can be labeled “Made In Germany” or “final assembly in (insert country here)” and merely reading that location has the power to dramatically alter the perception of quality, just as something simple like how much a camera or lens weighs has to do with quality “feel” much more than it does with actual quality. People are also likely to feel that cameras made in Japan are superior in quality to those from Vietnam, Thailand or China. Is this based on experience, hearsay, assumptions or statistical data? Those of us who care about workers being paid properly prefer to see cameras made in countries where labor is respected rather than in countries where assembly workers are exploited in the name of profit, but the manufacturing process is generally highly scripted and/or automated, making the country of origin secondary at best.

So why have I been talking so much about assumptions and misconceptions? Well, the same assumptions about image quality, dynamic range, “noise,” sharpness, character, tonal depth and various other qualities are immediately drawn when one begins talking about photographic formats. A term commonly used in marketing today is “full frame.” If you think about it in a pure sense, it’s a meaningless term based on arbitrary film format. When 35mm film came out, largely a conversion of movie film for the purpose of still photography. The original Leicas that used 35mm film, specifically to reduce the size of cameras below that of 8×10 and 4×5 view cameras, was perceived by many as low quality and not capable of “professional” results. Of course, the smaller cameras were embraced by those who wanted portability and the kind of real life moments that are now often referred to as “street photography.” Most of the images taken by the great masters of this genre, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Robert Frank, Rene Burri, Elliott Erwitt and most of the Magnum agency were taken with 35mm Leicas and often with nothing more than a 50mm lens.

“Photography has not changed since its origin except in its technical aspects, which for me are not important.”

– Henri Cartier-Bresson

Fast forward to the onset of digital photography. The first digital camera was invented in 1975, and Kodak later used a modified Nikon body for the Kodak DCS 1MP camera in 1991, but it wasn’t until the Nikon D1 DSLR from 1999 that the technology began to be embraced by working professionals. Although this camera was $5000 and only a 2.7MP sensor, immediately sports photographers and some photojournalists were using them. Double-page spreads appeared in print in magazines like Sports Illustrated and Time Magazine. Think about that when we start talking about the current obsession with pixel-peepers and file size later on…

In previous blog posts and public interviews, I’ve talked about my experience with medium format at 35mm film formats, as well as shooting “full frame” digital cameras like the original Canon 5D, as well as several APS-C formats like the Nikon D2Xs, D300 and I used the Fujifilm X-Series for 4 years until very recently. I won’t repeat that detail here for the sake of brevity. I prefer working with 3 bodies and prime lenses, which give me the speed I need in low light, and the wide/50/telephoto combo I’ve been using for most of my career means I can pre-visualize my results and know what I’m getting with the lenses I’m using. I rely on muscle memory to react quickly: wide angle (35) always on my left shoulder, normal (50) lens on my neck, short tele (85/90) or longer tele (150) on my right shoulder. If something happens in front of me that is far away, I know to reach for the camera on my right, etc. This has worked very well for me, regardless of the camera system as it’s been the one constant component to my approach to equipment.

Around 2012, when my Nikons were getting elderly after years of use, I started thinking about getting replacing them with two Nikon D700s as the used bodies were going relatively cheaply. At the same time, I’d been reading about the completely unique Fujifilm X-Pro1, which was about the same price as the Nikon D700 I was considering. The X-Pro1 also *looked* like the Leica M6/M7 bodies I’d been missing, and that lust led to my purchase of that body with the 35mm f1.4. As I noted in my long essay about my time with the Fujifilm system, the original X-Pro1 and 35 f1.4 began with buyers remorse as the AF with the original firmware was so slow as to be nearly useless, and the 35mm f1.4 had loud, chattering aperture blades and the lens made a dry, scraping sound when focusing as the center of the lens slowly pumped from minimum to maximum focus (and back again) while hunting for focus. I ended up bonding with the system, which luckily evolved through firmware updates into a very useful system, though I was never fully in love with their lenses, though I rather liked the 56mm f1.2 and the weather sealed 35mm f2 was a small, excellent lens. It seems like so long ago already, but mirrorless didn’t really begin until the Olympus E-P1 in (2009) and Fuji X100 (2011) came along and got people thinking about these smaller, quieter cameras. Since I had been shooting APS-C with the Nikons (after the FF Canon 5D), I didn’t consider the Olympus as I made the assumption that the M43 format was too small and not capable of the same results. It should be noted that this assumption wasn’t based on evidence and turned out to be wrong, but more on that later.

Last November, my original Fuji X-Pro1 (that I’d been using with the 23mm f1.4 lens) started displaying signs of dementia, refusing to shut off and sometimes showing the symbol that it was cleaning the sensor and writing to the memory card (orange light). I’d also sold my X100S, which was my 35mm equivalent, because I was using the X-Pro1 with the 23 f1.4.

I’d been reading about the Olympus Pen-F, a digital recreation of their legendary 1/2 frame film body from 1963. It was beautifully crafted (no visible screws, even) a solid build quality all metal body and had the rangefinder style body without the prism, as well as a 20MP sensor. I read some more about it and kept my eye out for a used one.

A BRIEF TANGENT: I like to buy locally, which is not only good for your local economy, which employs local people, but you also form a relationship with the shop. I consider myself lucky that National Camera in Minneapolis is particularly good, giving 6 month warranties on used cameras and even free loaners if they should ever need repair. They match online prices, (so there really is no need to buy online) and you get it immediately rather than waiting for shipping. If you are accustomed to buying online, give local a try if it’s an option for you in your town.

As luck would have it, I found a like new Olympus Pen-F begging me to buy it, along with a 17mm f1.8 (34mm in M43). I agonized over it for too long, worried about mixing an Olympus body and lens with my Fujifilm system as I prefer a streamlined system where I can not have to mix interfaces and body designs. There was a lot to love about this camera. For starters, it is BEAUTIFUL. It’s as close to a 60s vibe as you can get from a digital camera. I immediately dug in to the deep menu system and read everything I could about how to use it. Coming from my experience with other cameras, particularly the last 4 years with the Fujifilm system, there were a myriad of features that were new to me, most of which I didn’t expect to appreciate so much.

The first thing I noticed with the Olympus was the fast AF and speedy face recognition. I had spent the previous 4 years getting used to the slower AF of the Fuji system, which altered the way I worked, largely in positive ways. The Olympus would snap silently into focus rather than slowly hunt. You could choose focus point in several ways: the four-position keypad on the back (like the Fujifilm bodies), using the two main dials, letting the camera choose from all points, or with your finger on the touch screen of the rear LCD. You could drag your finder on the screen to track the subject AND even set the screen to fire the shutter from the touch screen. Coming from what I was used to, I didn’t understand the appeal of the touch screen and was dismissive of the need for it. The rear screen also was fully articulating, meaning it could flip out in nearly any direction to allow for easy shooting at unusual angles and even be flipped around to protect the screen when carrying the camera or putting it back in your bag. The touch screen has multiple uses: you can use it to select specific items from the menu system, and you can even flip through images with your fingertip as you would on an iPhone.

The next feature that I appreciated was the 5-axis IBIS (in-body image stabilization). Like the touch screen, I had no idea how useful this would be. In short, the sensor floats in a magnetic field and responds to the slightest bit of movement to hold the camera steady. I had very little experience with this in the past. The long lenses from Canon and Nikon (70-200, etc) that had it were very disorienting to me, even to the point of mild nausea. On the little Olympus with the 35mm equivalent lens, it was buttery smooth and extremely effective. Determined to see exactly *how* effective, I started doing test shots with slow shutter speeds. I’ve been able to get sharp images with the shutter as slow as 1 full second! Olympus claims a 5 stop boost, 6.5 stops in conjunction with in-lens IS. Some photographers like Robin Wong have been able to get sharp images from even longer exposures. Most photographers try to keep their ISO as low as possible when shooting to minimize noise. When you have a smaller sensor, one becomes more mindful of keeping the ISO low as the noise is theoretically higher with APS-C/M43 sensors vs 24mm x 36mm sensors. Obviously, moving subjects still require a shutter speed fast enough to stop the action, but with most other kinds of shooting, image stabilization allows you to keep ISO lower because the camera acts like it’s on a tripod. I’ve used other IS systems, and Olympus is in a class by themselves here, part of the benefit of the smaller sensor. It’s extremely effective, and as it’s in the body rather than the lenses, it means even manual focus lenses used with an adapter get the benefit of the 5-stop stabilization. Regardless of the situation, I leave the IBIS on all the time. When you have the camera to your eye, you hear a very faint whirring sound as the stabilization activates, but it’s completely inaudible to anyone else.

With every system I’ve used, I always prefer prime lenses. I like to know exactly what I’m going to get before I put the camera to my eye. Prime lenses are sharper, faster and smaller than zoom lenses. When you get to really know a focal length, it helps you pre-visualize your results: you start to “see” images in front of you with the two or three lenses you use most, and will instantly go to the one you need. Fixed focal lengths have faster maximum apertures, so you have greater control over depth of field, and get faster shutter speeds and lower ISOs than you would with zooms, which typically max out at f2.8. With APS-C, you gain a stop of DOF, so f2.8 means f4. With the M43 system, you gain two stops of DOF, so an f2.8 lens would still have f2.8 light gathering, but the DOF of an f5.6 aperture. Fortunately, M43 still allows shallow DOF with a full line of f1.2 , f1.4, f1.7 and f1.8 lenses.

Another advantage of Micro Four Thirds: Smaller lenses and access to the full line of Olympus lenses, Panasonic lenses, the Leica designed lenses made in partnership with Panasonic, as well as Sigma lenses and the countless number of lenses that can be used with adapters.

Since the original Olympus Pen F from 1963 and later the early 1970s Olympus OM-1 and OM-2 film bodies and Zuiko lenses, Olympus has overtly been drawn to the Leica optical design character. The original Zuiko 50mm f1.8 was a nearly perfect copy of the Leica 50 Summicron f2 lens in the way it smoothly rendered out of focus backgrounds. (The OM-1 was originally called the M-1 until Leica complained). The next morning after I bought the Pen-F, we got a November snow and I brought the camera out early and made a photograph of a snow covered bench in front of a lake, with the camera set to high contrast B&W with a yellow filter and the camera set to emulate a grainy film. The results were absolutely beautiful. The character of the image was timeless and the soft, smooth bokeh was like a rebirth of the pre-ASPH Leica 35mm Summicron. I WAS HOOKED. As yet another bonus, the B&W film emulation was actually rather good, too.

So, the seed was planted. I was loving the results and wanting more. It was like walking into a restaurant with low expectations and realizing you are enjoying one of the best meals you’ve ever had.

You realize that many of your judgments and assumptions are based on bias and emotion rather than facts and experience. We make emotional decisions all the time, but our brain wants us to believe they are based solely on reason and logic because we find that thought comforting.

I’m not here to convince you that M43 is the “best” or to switch to Micro Four Thirds, but I am going to explain to you why it works so well for me.

The one main complaint I had read about the Olympus bodies is also a benefit: the complicated menu system. There are several dials, buttons and switches that can be programmed to do anything you want. Yes, they are extensive and they are intimidating. At first, these menus were so overwhelming that it took me a while to even figure out how to switch into RAW shooting mode. The answer, like many other things with the menus, is that there are several ways and the best way is whatever works for you. You can save your configuration of settings in the “MySet” custom settings so you can have 4 completely different sets of adjustments made. I have no idea why anyone would want 4, but it’s an option if you are that kind of person. Fujifilm has the “Q” menu, Olympus has the “Super Control Panel” that you access simply by pushing “OK” on the rear of the camera. This controls image quality, AF options, drive speed, etc, but goes one better by allowing access to colored filters for B&W as well as access to tone curves for highlight and shadow. Once you activate these menus at the touch of a button, they are adjusted with the two main data dials that are normally used to adjust aperture and exposure compensation. It’s fast, shows a display of your changes with numerical values, and you can also see the results instantly in the EVF.

This is becoming a much longer article than I originally intended, so I’ll cut to the chase. The important thing is the results. The way I’m processing my RAW files with my custom settings, they look even more like my favorite film, Fuji Neopan 1600 than any other camera I’ve used. SOLD! I immediately started hunting for used versions of their former flagship, the awkwardly named but fast and robust camera, the OM-D E-M1 from 2013, the first mirrorless camera targeted to professionals, and the OM-D E-M5II, which is a smaller camera body clearly designed after the OM-2 film body, all the way to the pointy prism. I still have my OM-2 film camera and the 50mm f1.8 lens, but rarely shoot film anymore.

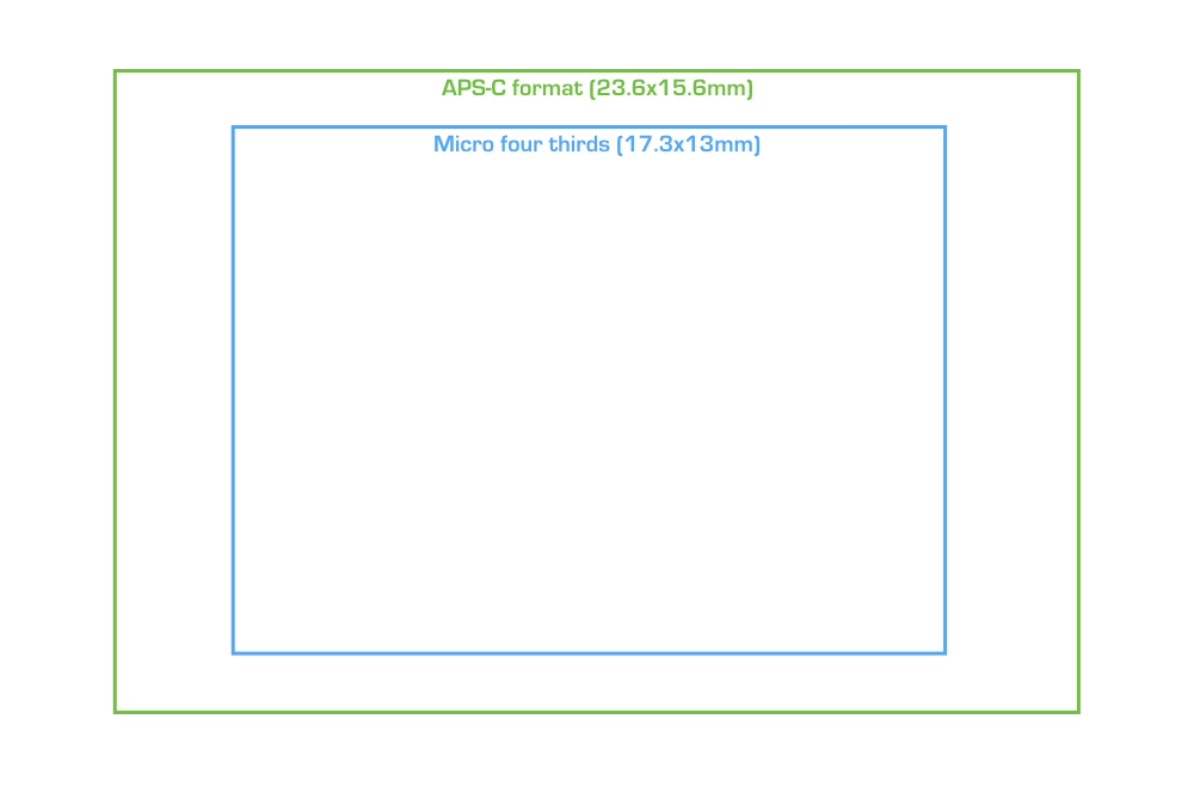

It is fairly universal that people think image quality is determined solely by the size of the sensor and the size of the file. In reality, it’s not that clear cut as every manufacturer adds their own “secret sauce” to the sensors that are almost always made by Sony anyway. For one thing, the M43 sensor’s 4:3 ratio is barely smaller than APS-C, and I discovered a hidden benefit in the native 4:3 ratio when processing RAW files. I set the cameras to shoot in 3:2 mode as I prefer the shape and I want all of my new work to match my old portfolio. There is also a tendency toward binary thinking and extreme comments in product reviews. One of the more extreme examples I’ve read said, essentially that APS-C is the same as 24×36, but Micro Four Thirds is more like an iPhone. “Observations” like these cannot be taken seriously, and are designed more to be deliberately inflammatory or as click bait to generate traffic. As you can see, the difference is sensor size is minor, not exponential.

After my first wedding where I used the Olympus Pen-F in conjunction with my old Fujifilm bodies, I imported the RAW files into Lightroom. I was looking at the Olympus files to see how they looked compared to the Fuji RAW files I’d been using for 4 years. Not only is there slightly MORE detail, but the color is better and more neutral. Gone is the color smearing that plagued the Fuji files, particularly with skin tones and green foliage, a byproduct of two things: the “X-Trans” sensor is really just their proprietary 36×36 color pattern overlay on the Sony made APS-C sensor rather than the normal Bayer color pattern, as well as the fact that Fuji has been burying NR in the chroma channel. (If you are curious, you can read more here: https://petapixel.com/2017/01/27/x-trans-promise-problem/). Fujifilm has been hiding NR in the files to reduce high ISO noise, a noble effort, but it can’t be turned off and it causes smearing in similar colors like lips and skin, causing them, on occasion, to yield dead skin tones that appear wooden or almost plastic. I always had gorgeous results converting Fuji files to B&W. They really pop. Dealing with color was never as easy until I found ways to mask these color problems in Lightroom, but they never went away completely. My portfolio has always been biased toward B&W, so this wasn’t as significant to me as a photographer who earns his/her living entirely in the color domain.

To see more examples of the detail than can be extracted from these files, check out this FF/APS-C/M43 comparison by Steve Huff: www.stevehuffphoto.com/2015/02/23/mirrorless-battle-micro-43-vs-aps-c-vs-full-frame/

To see examples of slow shutter speed performance (up to 5 second exposures handheld!) of the IBIS in the new E-M1 Mark II by Robin Wong: https://robinwong.blogspot.com/2016/11/olympus-om-d-e-m1-mark-ii-review.html

The unexpected surprise: My cameras are set to shoot in 3:2 mode, but of course, RAW is RAW so the Olympus ORF files remain 4:3 although they appear as 3:2 when imported into Lightroom CC. I was editing my first wedding with these files and a image I loved was cropped a little to aggressively on the groom’s hand. I clicked the crop tool in Lightroom and suddenly the 3:2 frame was surrounded by the original 4:3 file, showing the groom’s entire hand and all the other data from the “full frame.” I was able to keep the shot by altering the crop with this hidden extra data. It was like going back in time and shooting it again. Since then, I have photographed 5 other weddings entirely with Olympus cameras and lenses and used this hidden crop information a few times with great success. I will post an example of this when this article resurfaces in some form on my own blog.

The cameras and lenses are small and feel very balanced in use. I always have one with me, usually the E-M5II with the 17mm f1.8 lens, which acts like a 34mm lens. I use my two E-M1 bodies with the larger lenses, the 25mm f1.2 and the 75mm f1.8, both of which are world class lenses. I haven’t yet purchased the E-M1 Mk2, but I plan to in the near future, which adds phase detection AF, a 20MP sensor and a number of additional features including further improved high ISO performance.

I absolutely love the 50mm perspective, and with M43, you have at least 5 options (two from Olympus, two from Panasonic and a manual focus Voigtlander 25mm f0.95). I was a fan of the Fuji 35mm f2, which was small, cheap, light and weather sealed. It had the DOF of an f2.8 lens. While I love the small and light Olympus 25mm f1.8, their latest prime in the “Pro” series is possibly the best lens I’ve ever used from anyone: the 25mm f1.2. This lens is all metal, solid as a brick, weather sealed and has the manual focus clutch with a perfectly silky focus ring. Best of all, it’s tack sharp at f1.2 and has the most pleasing sharp to unsharp transition and bokeh I’ve ever seen (reminds me of the old pre-ASPH Leica 90mm Summicron). It is $1200 new and while larger than other M43 lenses, is still small by “full frame” standards. It also beats the Fuji 35 in focus speed and aperture, with light gathering of an ultrafast f1.2 (1.5 stops faster than f2) and f2.4 DOF (1/2 stop shallower DOF than the Fuji 35mm f2). This lens is permanently fixed to one of my EM1 bodies and is my most-used lens at weddings. I could do an entire wedding with this lens.

Since my first wedding, particularly when I started shooting with Leica lenses, I’ve been using mainly the 35/50/90 trio of primes, 35 being as wide as I needed with rare exception. With M43, I almost bought the Panasonic/Leica 42.5mm f1.2 lens (universally highly regarded) until I saw the Olympus 75mm f1.8. This lens, smaller than the 25mm f1.2, is the equivalent of 150mm telephoto. I don’t care for the overused phrase “game changer,” but my trio of preferred lenses is now 35/50/150, with a 90 in the camera bag that never gets used. I cover most of the wedding with the 25mm f1.2 (“50”) and when I need tight compositions and am stuck far away (staying invisible at the wedding ceremony, candid moments during the cocktail hour), the 75mm f1.8 (“150”) is priceless, and in the spirit of their other primes, renders detail sharply and out of focus areas in a very classic, smooth, pre-aspherical lens way like the old Leica 90mm f2 Summicron did. On the topic of lenses, Panasonic primes are also excellent, and some of them (the 12mm, 15mm, 25mm, 42.5mm) are made in conjunction with Leica designs, so the choice of excellent lenses for M43 photographers is larger than any other mirrorless format. Voigtlander even makes 3 all-metal manual focus primes for the system, popular with videographers with their fast f0.95 maximum apertures.

The style and quality of the re-creation of the Olympus Pen-F and 17mm f1.8 lens was my gateway drug to the system, but the handling and image quality of the four-year-old E-M and the quality of the lenses sold me on the system. I regularly see advertising and product claims paying lip-service to “pleasing bokeh” with references to “9-rounded aperture blades” and nonsense like that, but it’s really a byproduct of lens design and not trivialities like the shape of the lens opening. (Furthermore, the aperture blades only engage when the lenses are stopped down, so this would be completely irrelevant when shooting wide open). Only Olympus and the Panasonic/Leica designs actually deliver the classic image quality of older Leica lenses with the sharpness of modern lenses, and at very modest prices. No one else is doing that.

It’s way too late for me to say “in short,” but while bicycling with my friend John, I thought of a fitting analogy. John was the person largely responsible for getting me into 100 mile rides and fast group rides. We are both experienced bicyclists, used to riding in all weather from extreme humidity and heat (100F) to rain and winter snow and bone chilling cold (0F). Whatever the situation, you adapt to it because the important thing is the pleasure of the ride, not the bike. He has mostly carbon fiber bikes with top of the line electronic shifting, while I prefer my old mid-grade steel-framed road bike with high end components. While stylish, it’s not about style and doesn’t win any spec sheet competition, nor will it impress anyone with its lightness. It is extremely smooth and comfortable, handles like a sports car and just feels exactly like I want it to feel and that’s exactly what I love about it. I know how it will respond in any situation and I love the things that make it unique.

The M43 system is like that: it’s tempting to point exclusively to tangible elements like sensor size (like bike weight) and miss things like how the camera feels or how the lenses render (like bike handling/ride quality). It’s not going to work for everyone, and for people who need gigantic files and completely noiseless images at ISO 12800, you would be better served with a Sony A7s or A9 series, but then you are looking at up to $4500 for a camera with large, heavy DSLR sized lenses.

There are always tradeoffs. The M43 system gives me images that match my film portfolio, the camera and lenses are lightweight, have professional build quality, and are a fraction of the price of other systems.

I’m getting exactly what I want, and most importantly, I’m doing my best work ever, which is the point of photography: creating images that cause an emotional connection with the viewer (or your clients).

Rather than writing about this forever, I’ll end on this tedious bullet list:

GOOD

- Small, solid bodies are splash-proof, dust-proof and freeze-proof

- Autofocus is fast and AF point can be chosen in multiple ways or manually overridden

- Touch screen makes using the camera easier and is better for viewing images

- Fully articulated screen more versatile than one fixed to the back of the camera

- 4:3 native format can be altered to be 3:2, 16:9 or 1:1

- Fine detail surprisingly higher than 16MP Fujifilm APS-C files

- Huge collection of native lenses from Olympus, Panasonic, Voigtlander, Sigma, Samyang, Mitakon and others (more than any other mirrorless system)

- High ISO noise looks more organic and random like film grain than Fujifilm RAW files

- Shallow DOF easily achievable though less flexible than larger formats

- Lenses more affordable and everything is cheap on the used market (other than E-M1 MkII)-Elaborate menu system is endlessly configurable to your needs

- Camera and lenses even smaller than APS-C (some exceptions)

- Battery life almost twice as long as Fujifilm batteries (600 shots per battery with EVF off)

- E-M1 MkII and Pen-F high res mode provides 50MP file (though requires tripod)

- I love the manual focus clutch on the 12mm f2, 17mm f1.8 and 25mm f1.2 lenses

- Like Fujifilm, regularly firmware updates add new features

- Extremely easy to update firmware with USB cable and Olympus app

- Greater DOF at every aperture means faster shutter speed

- Image stabilization for video is unbelievably good

NOT AS GOOD

- Face recognition drawn toward heads with both eyes visible, so it may grab background faces

- Loss of 1/2 stop of dynamic range vs APS-C and 1 stop vs 24×36 sensors

- Shallow DOF still achievable though less flexible (two stops more DOF than 24×36 sensors)

- Noise about 1 stop more than Fujifilm APS-C files, but largely due to Fujifilm’s hidden NR

- Tracking of moving subjects isn’t perfect and AF-C isn’t ideal

- Menu system complicated and non-intuitive to most users

- Fast wide angles and normal lenses may be larger than their APS-C equivalents

- Almost impossible to find a camera shop that rents M43 equipment

- High-Res mode requires a tripod and ideally, no movement (landscape, architecture, etc)

- I wish there was a panorama mode or 2:1 crop

- I prefer the older tilt screen of the E-M1 to the fully articulated one on the Pen-F and E-M1 MkII

- While the ISO option is one click away, a dedicated ISO dial would be preferable

- Why doesn’t every prime lens have the manual focus clutch?

- Touch screen would be even more useful if zooming into the image could be done with fingertips

- Diffraction occurs at smaller apertures, but greater DOF means you don’t need to stop down

In 1999, Bradley embraced the natural, un-posed method of photographing weddings that came to be known as wedding photojournalism. Bradley’s candid, documentary style approach to weddings is to be as invisible as possible and capture beautiful moments of emotion as they are happening, rather than creating them. Working spontaneously, he takes a very compositional focus to his work that is a mix of abstract and minimalist.

José Geraldo

June 21, 2020 @ 01:56

Artigo muito interessante. Palavras verdadeiras de um profissional real, com nível de qualidade e experiência em eventos. Obrigado.

Bradley

June 21, 2020 @ 13:15

Thank you, Jose!

Best,

Bradley

Alex Galimov

June 21, 2020 @ 05:19

As a long time Olympus user (since their first 4/3 Evolt model), I greatly enjoyed your article. Very well summarized! Thank you for penning this article.

Bradley

June 21, 2020 @ 13:06

Thank you, Alex. It had been so long since I wrote this in one sitting that I had forgotten what I said. I still stand by all of it, even though I no longer shoot M43. I have enormous respect for the Olympus and Panasonic lines. I hope they make it. For 99% of all shooting, it’s ideal. The EM5 series with the 17mm f1.8 is such a perfect daily camera because of the size and ergonomics.

Stephen de Souza

June 21, 2020 @ 08:36

Thanks. Great article. I love my EM1 and PEN9. Given you are a cyclist too, what’s your recommendation on a camera to take cycling? I’ve found the PEN a bit big but would like something better than my phone!

Bradley

June 21, 2020 @ 13:08

Good morning, Stephen-

I honestly use my iPhone 11 for most of my bike rides because it fits in the back of my jersey/coat pocket and the stills and video and shockingly good, but my favorite portable camera is still the EM5II + 17mm f1.8 because it’s small and perfect ergonomically. On long rides, I don’t want a camera flopping around my shoulder, so you can tuck it in a bike bag.

Best,

Bradley

Stephen de Souza

August 30, 2020 @ 22:45

Thanks for your responses. I actually invested in a small bar bag (much cheaper than another camera) on your advice and my PEN fits perfectly in there, so I’ve found I can take a camera on more rides and it works well.

Bradley

June 21, 2020 @ 13:18

PS- Another great option would be any of the Sony A6000 series, which is APS-C, very small, very fast AF and small primes. I see the older ones at very low prices, but you’d have to get into another set of lenses (or at least one) in addition to your Oly gear.

Mike Abbott

June 21, 2020 @ 10:40

I embraced the micro 4/3rds system at least 8 years ago now, and have never looked back. It is as you say, ‘Horses for courses with camera gear.

Being an amateur nature photographer, 4/3rds has distinct advantages, especially with the crop factor and telephoto lenses. I went for Panasonic, as i like to do video too, and i think they make the best hybrid cameras.

I’ve never had a problem with image quality, and 16mp is more than enough for my needs, although they are using 20mp+ sensors now.

Also some very useful features such as being able to extract stills from video (4/6K photo) and focus stacking and post focus. These aren’t gimmicks, they’ve helped me obtain probably otherwise impossible images.

Thanks for a thought provoking article.

I think micro 4/3rds still has a long way to go yet, and certainly isn’t dead, as some would have us believe.

Bradley

June 21, 2020 @ 13:13

Hi Mike-

Yes. It’s probably pretty overwhelming for people choosing a camera these days because there are so many choices and so much misinformation. I overhear a lot of conversations while at camera shops that I stay out of, but we all have our biases based on our own experience. Everyone makes great cameras these days, so my advice remains to just find something that works for you and stick with it. All companies, especially camera makers, want you to feel like you need to be in a regular upgrade loop like a computer, tablet or phone. I sometimes buy new, but prefer to buy previous generation cameras when the new ones are released because everyone is dumping their barely used old cameras…

Best,

Bradley

Bradley

June 23, 2020 @ 18:09

Thank you for taking the time to read and comment.

Best,

Bradley

Bradley

June 25, 2020 @ 16:06

Although I no longer use Olympus equipment, I was saddened to learn that they are closing their photography division as of yesterday. I have enormous respect for their history, their engineering, and the amazing performance they’ve been able to squeeze out of that beautiful little sensor. I don’t think Panasonic’s M43 system will be long for the world, either, but I hope they can hang on. I’d guess that their S series full-frame line is a poor seller, and they’ve probably put a lot of resources into R&D and product development. Some speculated that trying to keep two product lines fed would be tough for Panasonic, and I agree with that. It’s a giant company with a lot of money, but they won’t keep shoveling money at a product line that is losing money.

The photography industry as a whole is in bad shape. iPhone and Android phones are getting exponentially better and they are already in everyone’s pocket. With photography becoming more ubiquitous and the tools becoming smaller and easier to carry, the role of portable cameras seems to be fading quickly.

Nikon is a medium sized company, but they’ve also had a long history of punching above their weight class. Their mirrorless system isn’t selling, even to current Nikon users. It’s going to be tough for them to generate sales when their DSLR users are sticking with the current system. After all the dust settles, it will probably be down to Sony and Canon, but I hope others make it, too.

John Simpson

June 27, 2020 @ 01:31

Nicely written; perfectly reasoned. What you wrote three years ago is more than ever true today.

We share many of the same thoughts.

Regards,

John Simpson

Bradley

June 27, 2020 @ 04:00

Thank you, John- I appreciate your comments. While most of the article isn’t specifically about Olympus, I was sad to learn that they are ending their photography equipment line. Fans of M43 will still have Panasonic (and the Olympus used market is going to be a better deal than ever), but the photography industry is in rough shape and all signs point to further erosion of camera sales…

Best,

Bradley

Michael Atlas

April 25, 2022 @ 15:21

Hey Bradley, stumbled upon this article and agree with many of the benefits of m43!

I have an E-M1 II, E-M5 III, many lenses, and a Ricoh GRIIIx. My m43 lenses:

PanaLeica 12/1.4

Olympus 17/1.8

PanaLeica 25/1.4 II

Olympus 45/1.2 Pro

Olympus 75/1.8

PanaLeica 8-18/2.8-4

Olympus 12-40/2.8 Pro

Panasonic 45-175/4-5.6 PZ

My workhorses are the 12-40, 25, and 45. The M.Zuiko Pro f/1.2 primes are incredible, but I could only bring myself to get the 45 as it’s an instant portraiture hero lens. The Oly 17/1.8 is nice enough especially for its size & price but the PanaLeica 25/1.4 is probably my most favorite lens after the Zuiko 45/1.2. Here’s a shot I took this weekend with the 25/1.4 + E-M5 III.

Lesly

July 19, 2020 @ 23:29

I was very sad to read that Olympus just left photography. I have always been a fan of Olympus cameras and their lenses are awesome.

I’ve just bought an EM5 Mark III, and found they have an impressive quantities of feature. Hopefully the new company will stick on this path and still produce M43.

Your article is very inspiring. And you made it right when you mention that at the end someone must choose a camera that fits his needs. Thanks for hammering that statement more and more

Bradley

July 21, 2020 @ 21:00

Hi Lesly-

Thanks for taking the time to read and respond. I think very highly of Olympus engineering and was also saddened to learn that they couldn’t make it. The smaller sensor does have some limitations in extremely low light, but for most applications, it’s a great choice that allows wide apertures and is very forgiving with focus errors. The EM5 series also has excellent ergonomics.

Best,

Bradley

subroto mukerji

April 5, 2021 @ 16:48

I use both an Olympus Epl5 and a Panasonic Lumix GX1, and love how the Lumix G 20mm f1.7 and Zuiko 45mm f1.8 render on them. It is hard to describe how wonderful are the images from this equipment. Attached is a heavily cropped shot taken with the Epl5 and the el Cheapo, plastic fantastic 40-150mm f3.5~5.6 Olympus lens; simply amazing, no?

I’ll keep using M43 as long as I can, I have no reason to switch back to Apsc. Thanks for your most interesting and inspiring piece.

— Subroto from New Delhi, India

Joao Oliveira

February 11, 2025 @ 12:56

Very interesting and accurate article. I was using an APS-C system before switching to MFT. My first MFT camera was the Panasonic Lumix GH5 which I bought to shoot video. Great little camera. Started using it for stills though on my weddings. Loved it so much that I sold all my APS-C gear and bought a Panasonic Lumix G9, another great little camera. Then, after almost one year I decided to go for the Olympus O-MD E-M1X because of the fact that it has contrast and phase detection autofocus. Although I hated the menu system and the EVF I loved everything else about it. Ended up buying a second one. Sold the GH5 and the G9 but kept the prime lenses. No regret. Well, regret not doing this earlier but it’s all a learning curve.