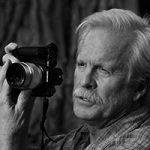

Interview with the Pulitzer-Prize winner and Olympus Visionary, Jay Dickman

Hello Jay! What an honor for us to have you for an interview. Would you like to start by introducing yourself?

Hi, I’m Jay Dickman. I’m a photojournalist/reportage/documentary/daily life photographer. I was fortunate to have won a Pulitzer Prize in photography, and I’m a National Geographic photographer.

What’s your story, since you discovered Photography to the day you became a full-time photographer?

Is this going to be a series? Wow, that’s a short question that creates a long answer. I’ll try to be brief: I’ve been in the business of professional photography for 40+ years–a fact that I really can’t quite grasp, as it’s been a long, drawn-out, blink of an eye.

I look back on the early to mid 1960’s as being the factor that drove my going into this business. I grew up with LIFE and National Geographic being my “window” to the world. As a kid, I’d look forward to the mail delivery of those two publications. These two publications, above all, were my ‘TV” set of those years. The NASA space missions, the Vietnam war, the race conflict boiling in our country, these were just a few of the extremely visual events that were presented in these magazines, by incredible photographers. In our home, we also had two copies of “US Camera at War” which contained photographs from WWII. Published in different years of the war, these books also contained immensely powerful imagery captured by many different photographers of that era. Looking at these publications, with their often incredibly powerful “frozen moments,” really impacted me. Early on, I was getting a college degree in the power of “moment.”

I grew up in Austin, Texas, and moved to Dallas in the mid 1960’s. I always loved books, and an English Lit teacher in my high school noticed that, and suggested that I should consider a career path in that discipline. I started my short college career at University of Texas at Arlington (UTA,) with the intent of getting an advanced degree in Literature with hopes of teaching. But that love of the still image was still in me.

In high school a buddy of mine had a motorcycle, a dirt bike. I couldn’t afford anything like that, but I’d ride on the back of his BSA Victor with him, as we’d head out to some of the many dirt trails found around Dallas. With my Kodak Instamatic, I’d photograph Kurt as he did jumps and other dirt bike moves. The local camera store was where I’d take that 24-exposure roll of film to be developed, and I’d anxiously wait out the few days until the 4×6” prints were ready. I’d find myself enthralled with certain images, especially those with a frozen moment: the bike frozen in mid-air, rear wheel seen spinning and throwing dirt off. Or him heading up a steep hill, with a look of determination on his face. These were my early and very feeble attempts to replicate those fantastic images that were burned in my memory from LIFE, or NG or “US Camera at War.”

During my time at UTA, I was working a paper route in the morning, driving out to school, homework and then working in the early stages of freelance photography: shooting model headshots, model portfolios and anything else that came down the pike. I also started becoming more enamored with the idea of being a pro photographer.

My parents wanted me to follow a more traditional career path: find a job with a company, dig in and do well, and many years later get a gold watch upon retirement. So, when I first suggested I wanted to be an English Lit major, that created friction…when I dropped the idea on them of wanting to be a freelance photojournalist, that about did them in. BUT, my Dad gave me a 35mm camera as my birthday gift (I think it was my 16th.) So, he did shoulder part of the blame!

I vividly remember the excitement of that first “real camera,” a Honeywell Pentax H1a. My first roll of film was B&W, and I assumed the way one chose exposure was to press the depth of field preview until the image looked “correct,” a very early histogram. Still, with no clue to exposure at this point, several of the images were correctly exposed which further deepened my love of the still image.

During the next months, I realized if I were to be a photojournalist I needed a portfolio. My early “book” consisted of a handful of prints, mostly landscapes, that wouldn’t get me anywhere today. I think it was my naive, youthful thinking that gave me the nerve to call a few of the freelance photographers in Dallas, asking if I could bring my “book” by for critique. Most were very polite, and I wonder now if I’d received a very harsh, brutally honest response my career in photography would have been stopped in its tracks.

I also convinced the news services, UPI & AP. to take a quick look. My personal “critical moment” came when I called the Dallas Times Herald (DTH) and convinced John Mazziotta, the Director of Photography, to look at my work. A silver-haired, seemingly gruff guy, John must have felt sorry for this kid who wanted to follow in his steps. He looked at my work, gave me a bit of critique, and then told me I needed sports in my book if I were to find work in newspaper photography. I’ve always felt I’ve had a Guardian Angel, or someone watching out for me, as I thought the natural way to find work as a sports photographer was to look in the newspaper’s classified ads for that job description. And if you think there were regular classified ads looking for that specifically-talented photographer, I’ve got a bridge I can sell you.

But, with a new direction in mind, I started looking at the classifieds. Here’s where that Guardian Angel comes in: as I recall, it wasn’t that much later, while perusing the classified ads, I found a listing under “Photographers Wanted” looking for “Sport photographer.” I called the guy, Rich, who’d just started a very small sports agency with intentions of covering local and central/north Texas-state sporting events. This would range from high school to the pros. He was willing to pay a few (very few) dollars to his hire, to drive to that game, photograph it, print 5-10 8×10” prints from that game, all on a deadline. The vetting process was very tough, the criteria steep. I had to win his approval from the field of other applicants, but this was made much easier as I was the only applicant. I was hired!

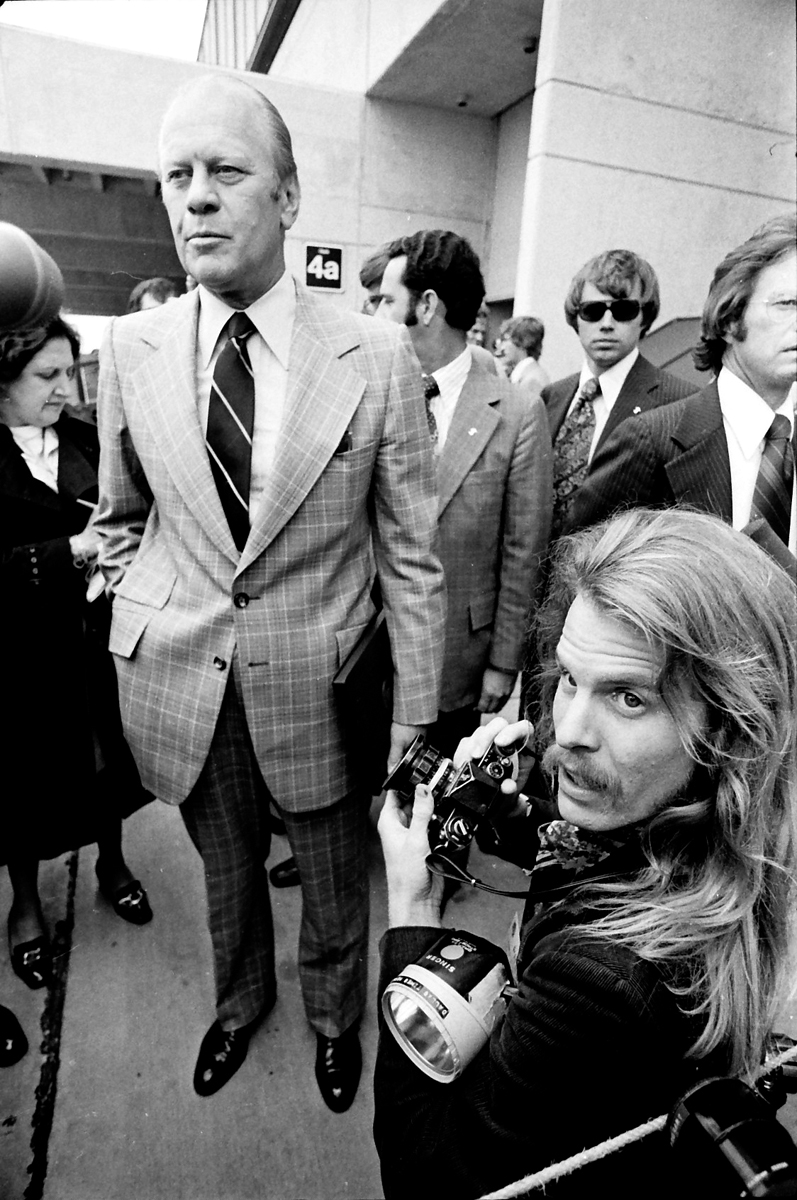

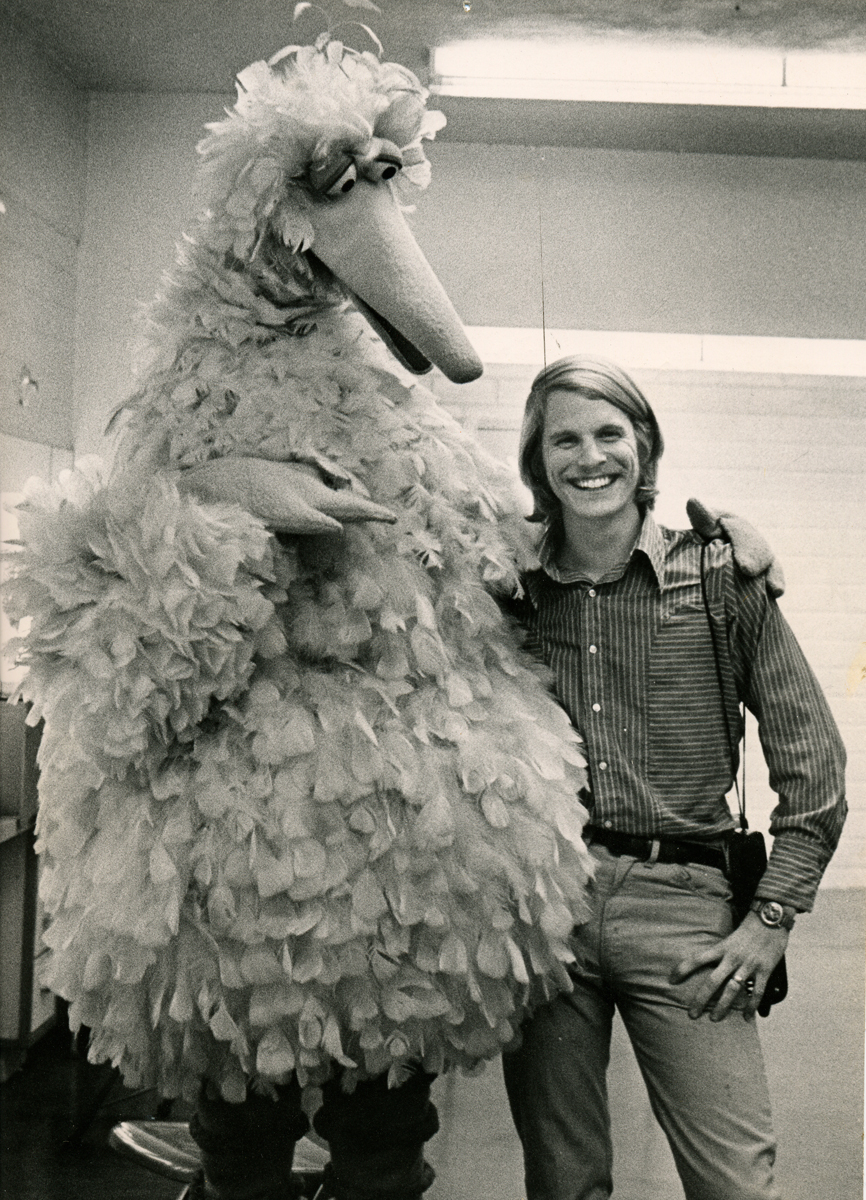

So, within a few months my book contained sports photography. I called John Mazziotta, told him I had a new book, and he politely made time for me again. The sports did the trick, as my portfolio worked. He said he’d keep me in mind, as there was not an opening at that time. I figured this was the end of my photo career, but in a couple of months he calls, telling me that a photographer had quit, and the opening was mine. Total freak out time. Now, things were real…he’d called on a Wednesday, asking me to show up on Monday. I remember the Friday before I was to join the staff, I had my hand on the telephone, ready to call him and back out as I felt I was too deeply in over my head. But something kept me from picking up the phone. Monday came, I went in, 21 years old and utterly terrified. The first DTH photographer to whom I was introduced was Bob Jackson, who just a few years before had taken the Pulitzer Prize winning photograph of Lee Harvey Oswald being shot by Jack Ruby. This confirmed that yes, I was in way over my head. But this became the learning experience of my life. I was immediately given several assignments to shoot that day, with no outlet or excuse of “I didn’t feel creative,” or “I wasn’t in the mood.” I had to produce, and produce several times a day. The learning process was great as the assignments varied from feature work to sports to spot news. What an amazing learning ground. I’ve been told that the majority of National Geographic Photographers come from newspaper backgrounds as they are taught to work with visual narrative within all disciplines of the newspaper world.

Among the several areas of Photography, why did you choose Photojournalism?

Referring to what I’d said above, I was always totally entranced by the “frozen moment,” especially in life.

The Pulitzer Prize from 1983 changed your career in any way? Could you tell a bit about the story from El Salvador?

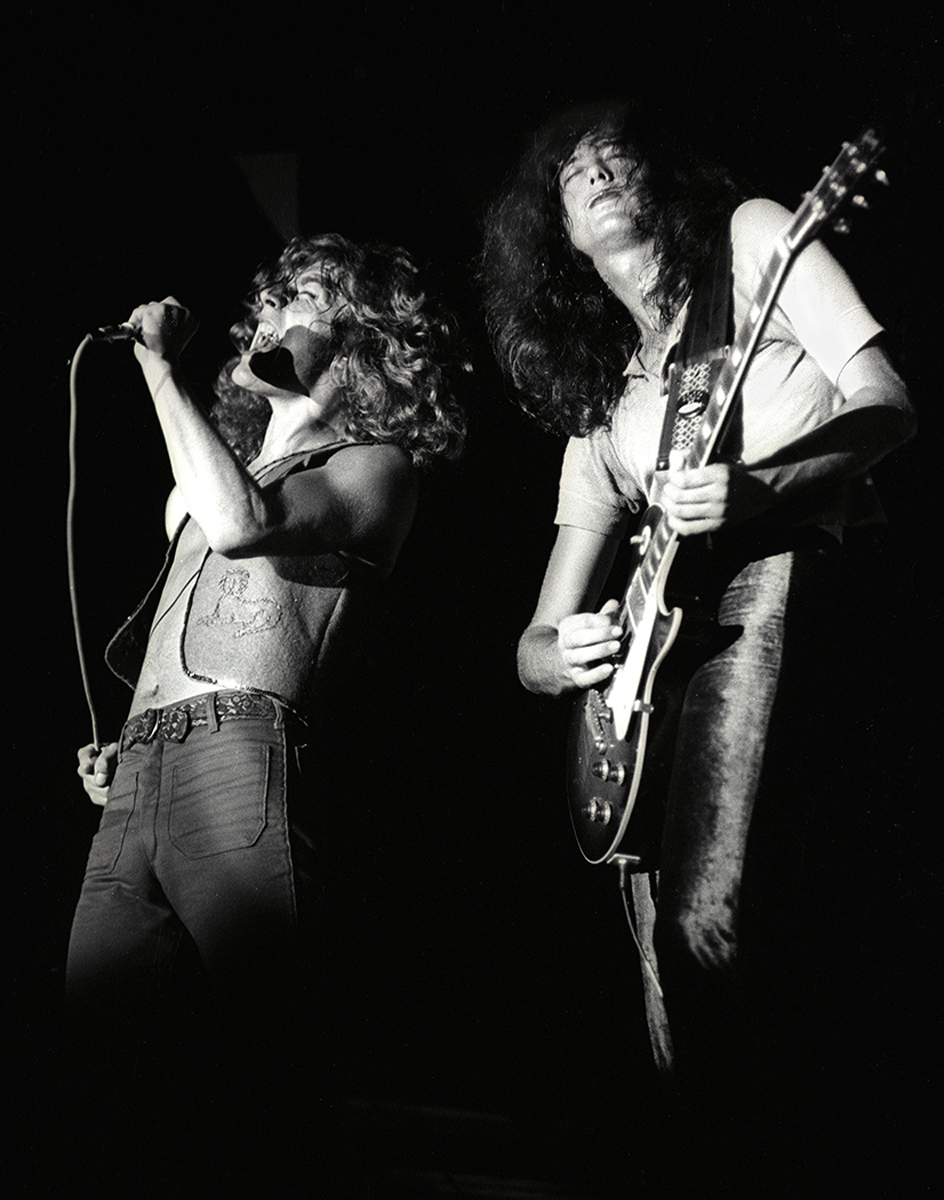

El Salvador was an “attractive” war, due to its proximity to the US. Young, inexperienced photographers could, in their eyes, cut their teeth on this nearby conflict. Flights were cheap, and the relative ease with which one could improve their book with war photography was a draw to some. The Dallas Times Herald decided to open a Central American bureau, based on the urging of DTH reporter, Bob Rivard. Bob saw the need for a bureau in this war-torn area, as what was happening there impacted our state and regional wide readership. The editor of the paper asked if I’d be interested in covering the war as part of the initial visual coverage of the conflict. By this time, 1982, I’d worked with the DTH for 12 years, and covered volatile situations in the spot news realm, so I felt my experience was valid and applicable to war photography.

I worked in El Salvador on three different occasions, spending a couple of months in the country. I worked with a couple of well-known war photographers, learning more of the tricks of the trade for this intensive coverage. I knew two photographers who were killed in the war, and both those were personally impactful upon me. I also had two very close calls myself, coming much closer to a fateful end than I hoped. Even with my experience, stateside, with volatile events (riots, hard spot news, events where one has to make a photograph when everything is out of, and beyond your control) covering a war was an entirely new experience for me. In those close calls, there was no dramatic music swelling in the background, no beautiful woman waiting for me in the hotel bar at the end of the day, it was just a crazy, out of control, insane event that was 360° and fully immersive.

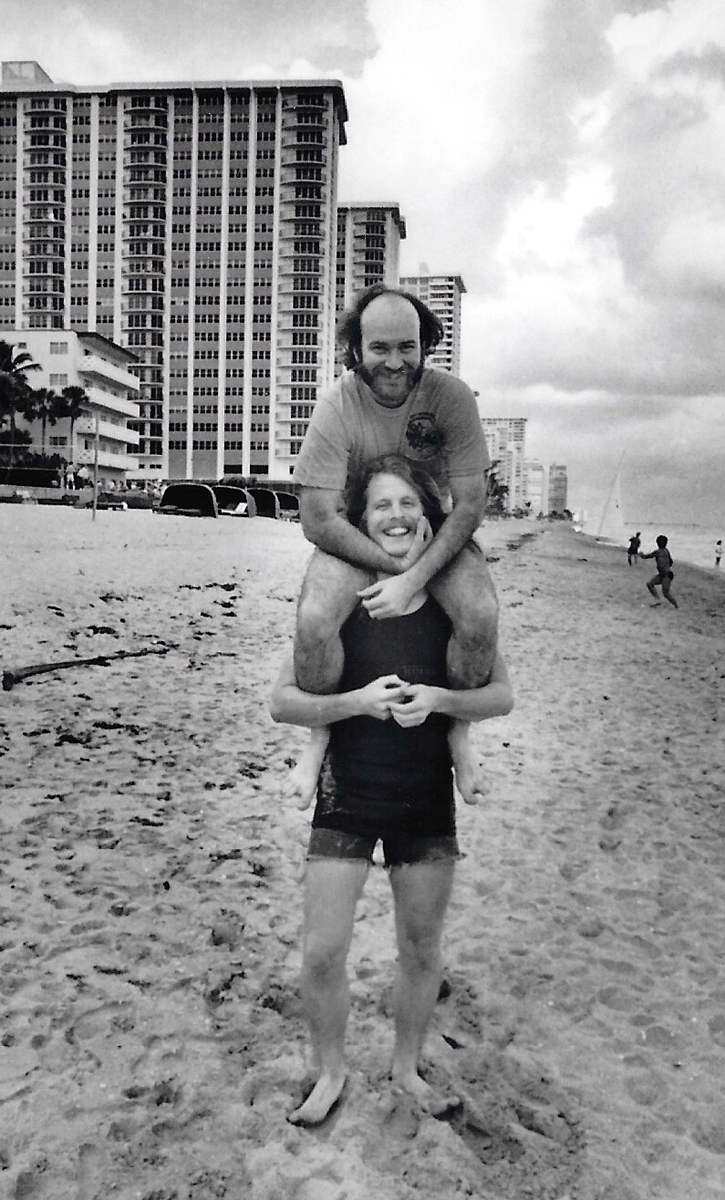

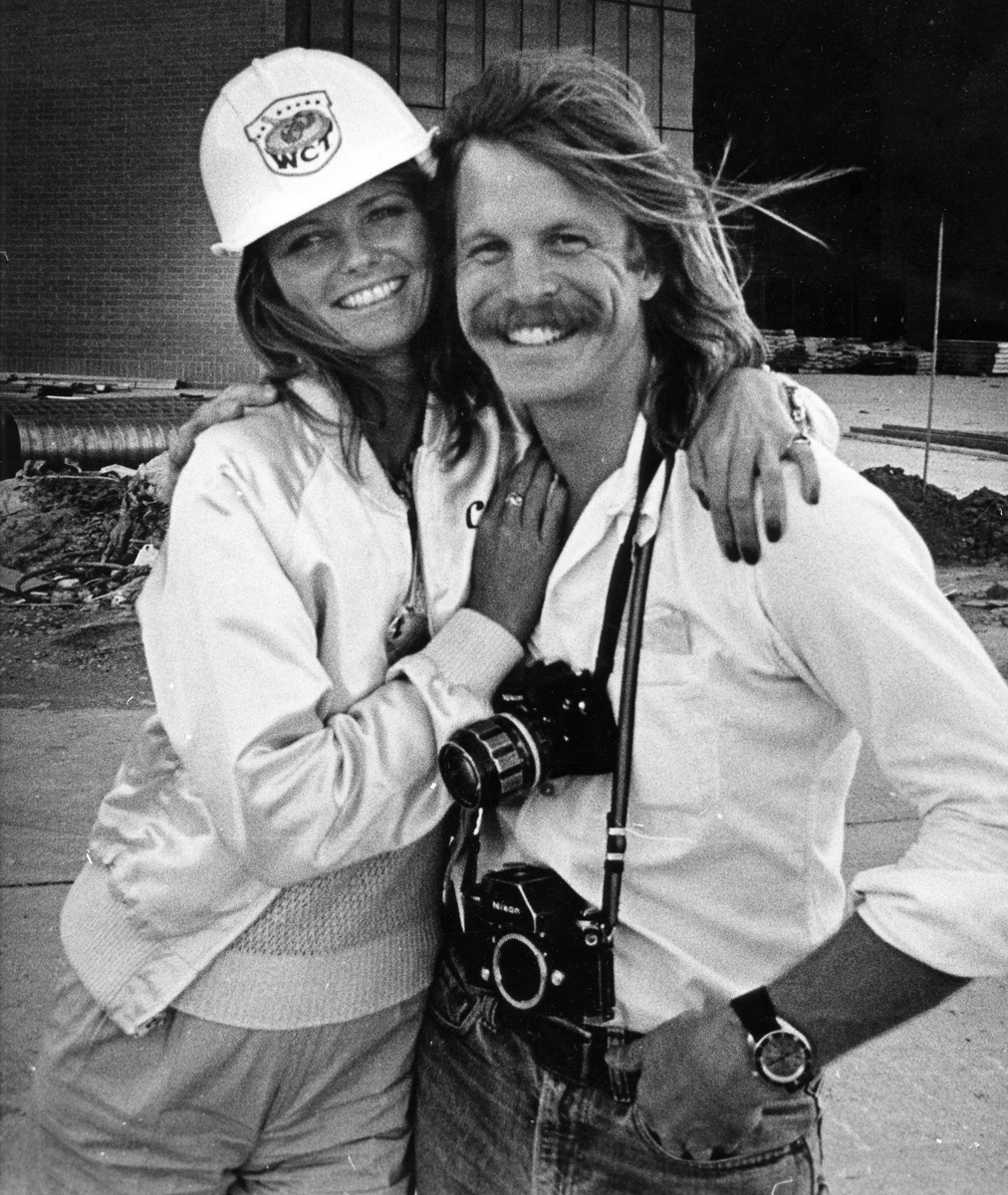

I submitted a 13-picture series to the Pulitzer committee, nominated by the Editor of the DTH. The day the Pulitzer’s were announced is burned in my memory: I was off that day, but was requested by Ray Adler, our Director of Photography, to come in “just in case.” Becky Skelton & I (fellow staff photographer & girlfriend that became wife & business partner) went in to the DTH late morning (the announcement is at 2PM central time) and hung out. We were all sitting in the photo department as the clock wound its way to 2. The phone rang, Ray answered, and then asked all of us to go to the City Room. It was a pretty surrealistic moment. Ken Johnson, the Executive Editor was standing there when we walked in, immediately calling out “Where’s Jay.” That was it, the moment. I remember I was at a loss for words, which is an unexpected state for me.

After winning the prize, the paper asked if I’d want to go to other hot spots, perhaps Beirut or South Africa, and one of those life decisions was presented. War/conflict photography can present the opportunity to make some very powerful and potentially important photographs. I think adrenaline must be as addictive as heroin–when you are in that dangerous moment, when things are out of control and you are still able to make powerful photographs that are of your style and contain a narrative, that is a powerful draw.

But, I never considered myself a war photographer; I was a photographer covering a war. Nor was I a sports photographer when I was photographing the NFL, I was a photographer covering sports. I tried early on to approach an assignment with the idea that every situation has its best moment. This is still true, still what I love about this craft of photography. I consider myself a generalist, which I also still love: the variety and demand is always there to make your best photo out of every opportunity.

From conflict scenarios to National Geographic Expeditions, you have been through some physically and mentally exhausting situations. What motivated you to always go for the next assignment?

My works today involves travel and location work. Last year I photographed in a total of 31 countries. International travel is no longer fun, it’s a grueling and exhausting experience. When I’m preparing for heading out on an assignment, I often get bummed-out, not wanting to leave my wife, our home, our daily life. At that point, when blue about having to leave, I go through a regular drill: I’ll pick up my camera, and there is still an electricity that goes through me, I get to do this. If that feeling ever goes, I’ll have to get a real job.

So, I think the most simple and direct answer to your question: my motivation has always been the potential of the next picture.

Would you have done anything differently in your career?

Really nothing as I feel incredibly fortunate with how my career has evolved.

Over these last decades we imagine that dozens of cameras passed by your hands and were pushed to the limits in the most harsh conditions. Which reasons led you to make the Olympus m43 system your current choice?

Awesome, as I’ll step up on my soapbox. Olympus had approached me in 2003 asking if I’d be one of their sponsored pros. John Knaur, the head of the pro program, gave me Olympus’ road map, where they were going in equipment design and ergonomics. Their intent was to return to a much smaller, friendlier system that one could carry for extended periods. This made complete sense to me, as I’d always admired the Olympus OM cameras back in film days. Compact and jewel-like in their construction, that design ethic made sense to me.

I’m still a sponsored Olympus Pro, an “Olympus Visionary”. I obviously feel strongly that the Olympus gear meets my criteria as a pro, which means it’s highly portable, great ergonomics, produces incredibly high quality and is there when I need it.

So, I started my alliance with Olympus, and I was thrilled when the MFT system came into being. Oskar Barnack had designed the original 35mm Leica back the 1920’s with the design ethic of small, compact, unobtrusive and capable of extremely high quality. I saw the same ethic with the MFT system. With the 2:1 crop factor, the Olympus and other MFT camera lenses are essentially halved in size and weight. Until the law of physics is changed, what will ultimately determine the size and weight of one’s camera kit will be the lenses. The Olympus 40-150mm f2.8 provides the field of view of a full-frame 80-300mm, and is considerably smaller and much more inviting to carry for long periods. What’s the best camera? The one that’s in your hands when you need it. I almost always work with two cameras on me, hanging from a BlackRapid Duo strap. One camera has either a 12-40mm f2.8 or the new 12-100mm f4 lens, the other the 40-150mm f2.8. And, unless sports or wildlife specific, these two lenses can accomplish 99% of my photographic needs.

Realistically I’m reducing the amount of gear I’m carrying as I often don’t carry a bag. A couple of extra batteries and everything becomes about focusing (no pun intended) on moment and the image, which drives everything in photography.

As the sensor technology moves forward, the quality of the image from the MFT sensor is incredible. I have prints hanging in our home, shot with an MFT Olympus, that are 50” on the long side, and the quality is stunning. If one argues the need for a FX sensor because of the need for quality, then their argument should follow that you should be shooting a medium format camera as that sensor is better, or better yet, a large format leaf-back, as that quality is better still. Every camera is a compromise, and one needs to filter/determine their own needs and let that drive the decision making. My world of photography is all about moment, image quality, and real-world portability; the MFT system is a perfect synchronicity of those requirements.

After using pro level DSLRs, now with Olympus mirrorless cameras do you feel the same amount of confidence in your equipment when stepping out to a highly demanding assignment? Or it’s more like a good compromise between image quality, lightness and ruggedness?

Yep.

Do you agree that having a lighter camera setup, you are able to maintain your focus in the photo assignment for a longer period?

Absolutely and positively. My aim for a camera is to have its controls so intuitive and accessible that the camera “gets out of the way.” The Olympus OM-D E-M1 MkII has become as close to an extension of my eye as any camera I’ve ever used.

Despite in the past the 6×4.5, 6×6 and 6×7 were usual aspect ratios, for many years the 3:2 has been the “standard” because of the 35mm film. Was it easy to adapt your sight to frame the photos in 4:3 format?

Having come from the film world, I would often work with 2 ¼ x 2 ¼, 645 or whatever I needed for the shoot. It was a bit strange at first going to a slightly more square format, but the transition was painless and quick. Plus, in a double-page spread in many magazines, including National Geographic, a 4:3 ratio file fits, almost perfectly, the spread. When Oskar Barnack invented the original 35mm Leica so many decades ago, his choice for the ideal film and format had to do with what was available and what had sprocket holes, thus the reason 35mm became the small format preferred size; it was not based on aesthetics.

Looking at your recent portfolio, what is the camera and lens combination used the most?

Most often, I find I use the 12-40mm f2.8, the 12-100mm f4 (a new lens to my kit. I’m finding I go to this lens more and more, and I find it an ideal “all in one” for knocking around with one camera body) and the 40-150mm f2.8. One lens that finds its way into my pocket, the 7-14mm f2.8.

Thank you very much for your time and attention! before saying goodbye, could you please leave final words to the young photographers pursuing a career in Photojournalism?

Very realistically, this is a tough business these days. Newspapers and other “dead-tree” publications on the printed page are seeing their numbers decrease. My best suggestion to the new, upcoming photojournalist: master multimedia as this skill set is so important and relevant to an image-maker in today’s market. Your parents are going to love this one: if you are in school, take advantage of every learning opportunity you can. Languages, liberal arts, business are all important areas of knowledge. Knowing how to speak other languages is an obvious attractant for a prospective hire to a pub that works world-wide. Liberal arts helps you learn how to write, and write well, proposals, grant applications, etc. And business… yep, this is a cool business, but it’s a BUSINESS. If you don’t learn how to run your finances, how to manage that money coming in and out, you will fail. Good luck, it is an amazing business as it allows you to view other cultures, lives, people under that veneer of tourism, and isn’t that why we travel?

JOIN OUR FACEBOOK GROUP

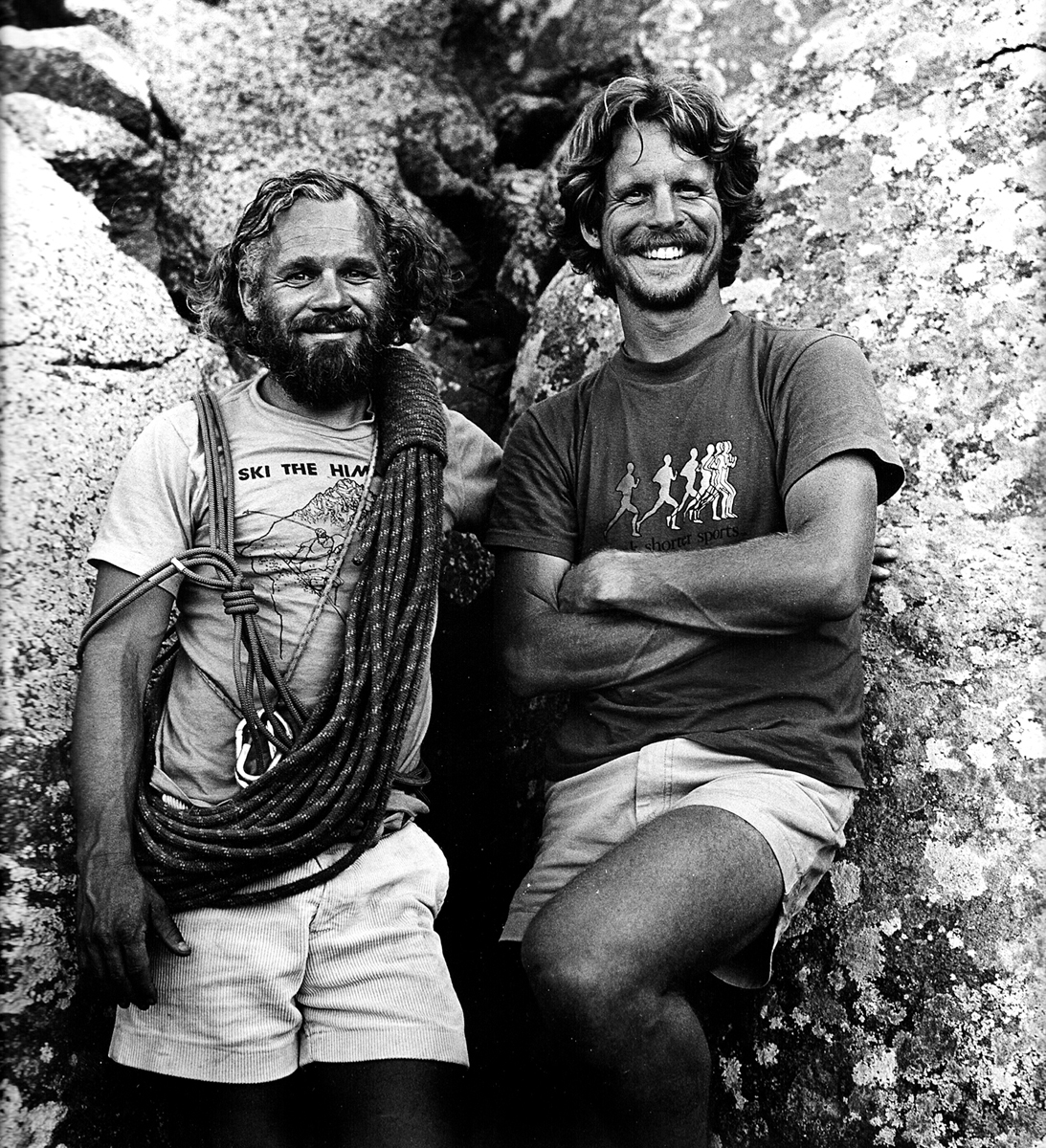

A Pulitzer-Prize winner and National Geographic Photographer, Jay’s career has spanned a multitude of experiences, including three months living in a stone-age village in Papua New Guinea, a week under the Arctic ice in a nuclear attack sub (both these for National Geographic), and aboard a sinking boat on the Amazon. With more than twenty-five assignments for the National Geographic Society, Jay has taught workshops for Santa Fe Workshops, the Maine Media Workshops, Photography at the Summit and American Photo Mentor Series. Jay and his wife, Becky, are founders of the FirstLight Workshop series, having hosted workshops in Italy, Spain, Scotland, France, the Chesapeake, and Wyoming.